“These phenomena constantly change and do not abide. They are like a drip of morning dew; as soon the sun emerges, they disappear. They are like water flowing from the mountains; they only go and never return.”

—Mahayana Jeweled Cloud Sutra | Fascicle Two | Chapter on the Ten Perfections

This quote exemplifies the meaning behind this blog’s name. Every friend I meet—every laugh, tear, challenge, and success I experience here are ultimately droplets of dew on the morning grass, disappearing almost as soon as they form. However, their existence is not completely in vain. They moisten the ground, nourish the plants, and freshen the morning air.

Tonight, two new drops of dew formed while one drop of dew evaporated into the air.

My two suitemates came home today, and Sangwon said somewhat awkwardly, “Wang Liang wants to tell you something.”

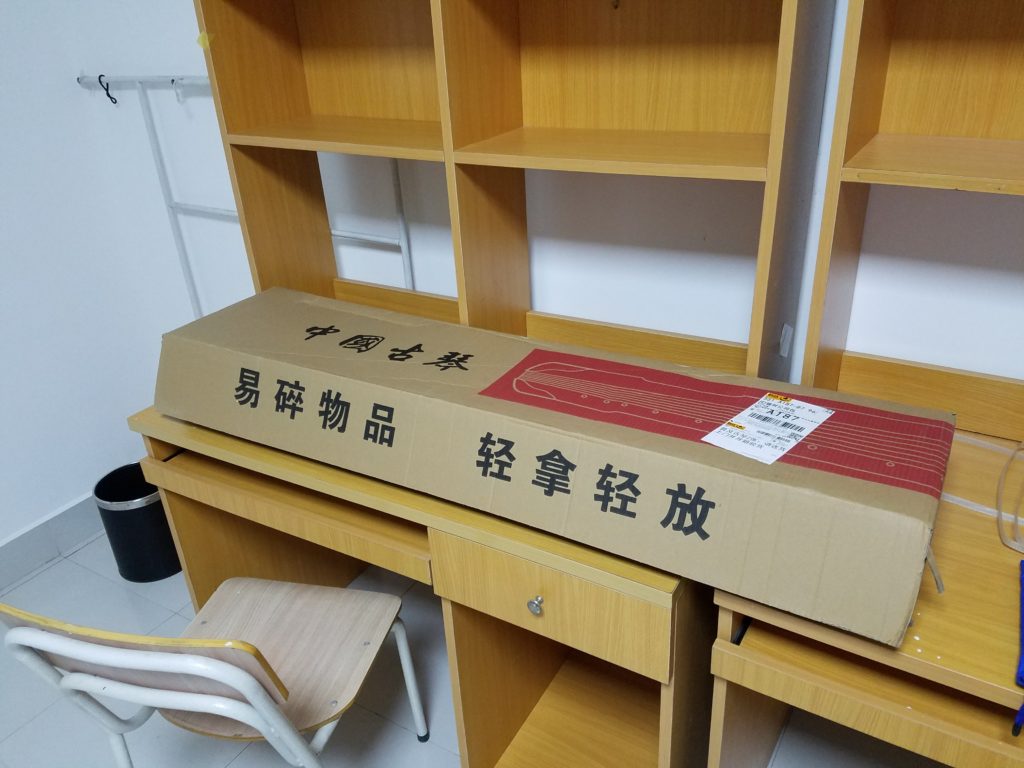

I turned over to him, my mind wondering what it could possibly be about. Was it that he was sick of hearing my guqin? Did I forget to flush the toilet at some point? Was he upset over me knocking his clothes over twice the other day?

“I don’t know how to tell you this,” he started. “But I have to go to the hospital.”

“What?” my mind began racing. “We should go. There’s one down the street. Is this an emergency? Are you okay?”

“We just came back from that hospital. They can’t treat me,” he said solemnly.

I felt like I was staring at a man who had already resigned to his imminent death. He carried no sense of urgency in his voice despite discussing a topic that revolved around needing to get to a hospital.

“Here,” he said ever so calmly. “Take a look at this.”

He passed me a stack of papers—his medical evaluation form. He was ill. Seriously ill.

“Don’t worry,” he assured. “It’s chronic. But they told me that if I don’t get treatment, then I can’t stay in the country. I’ll have to go back home.”

“Home?” I asked incredulously. “What about your scholarship?”

“I’m not sure,” his voice wavered. “I can always try again next year.”

My heart sunk. He had worked so hard to get here; he had spent so much time and effort to study. He was by far the most studious and serious person in our suite. And now, obstructed by an illness, he’d have to go home?

He showed me his recent correspondence with the graduate program advisor. She had given him a number to call and instructions to ask if our student insurance would cover the cost of treatment.

There was one issue: none of us had received our insurance information yet.

“Do you want me to call?” I offered.

“Thanks,” he replied. “But not now. I’m gonna discuss things with my family first.”

We didn’t have time.

Sangwon reminded us that it was 6 pm, and we had made plans earlier today to get dinner with a few of the other graduate students. I knew most of them by now, but there were two unfamiliar faces: May from Malaysia and Yongqi from Indonesia.

Having spoken Mandarin since they were young, the two of them were incredibly fluent, and I realized they must be bored to death in the HSK prep classes all international students are required to take. Indeed, as I walked with Sangwon and Wang Liang, I overheard them complaining about the inflexibility of school bureaucracy and how terribly this was planned. There were also multiple comments on how their instructor had a habit of talking down to them. An unfortunate situation.

Wang Liang decided it would be nice to go out for dinner. And so we walked. And walked. And walked until Yongqi finally asked, “Didn’t you say this place was only a few minutes away?”

“Yeah,” Wang Liang replied. “It’s only been a few minutes.”

Indeed, it had been roughly 20 minutes. Perhaps more than a few, but still in the range of minutes. Although we were all starving by now, our spirits were still high—or at least Yongqi and May were in high spirits, and that tended to rub off on the rest of us.

“Hey handsome!” Yongqi exclaimed.

I turned around, “What’s up?”

The others laughed, “Oh, you go by handsome now?”

“Why not?” I laughed in response.

“Hey,” Yongqi butted in. “I only called you handsome because I don’t know your name yet. What’s your name?”

“Andrew—”

“AH!” she stopped in her tracks. “I KNOW YOU!”

“You do?” I was very confused. I had never seen her before in my life.

“Yes! Everybody knows you. You’re all over the groupchat.”

Ah. Yes. That’s true. I am quite active on the groupchat.

This reminded me of my first year at Pomona College. While I was somewhat a quiet enigma on campus, everybody seemed to know me from Facebook.

We got to the row of restaurants, honestly not too different from the places that were only three minutes away from campus. But we were starving, so we ordered and feasted.

At some point during the meal, Yongqi complained that all of her suitemates had gotten into relationships and no longer had time to hang out with her. May suggested that she find herself a boyfriend as well.

“I haven’t found somebody my type yet,” she explained.

“Well, what’s your type?” May prodded.

“First, they have to be older.”

“There are three single guys here, all of them are older than you,” May gestured at the three of us.

“They also have to be international.”

“Yes… we’re all international here.”

“I meant like… America international. Not from an Asian country.”

Sangwon’s eyes lit up, “Him! Him! Him!”

“What?” Yongqi looked very confused.

“He’s from the US!” Sangwon said with a smile, both hands pointing straight at me.

“You?” she said.

“Yeah… I’m from the US,” I replied sheepishly.

“I was thinking someone who’s… blond. Not someone who looks like they were born and raised in SE Asia.”

Do I really seem that un-American? I was supposed to be a “cultural ambassador” for Fulbright and that didn’t seem to be happening because nobody associated me with American culture in the slightest.

Yongqi shook her head, “Sorry, but I’ll keep looking. Let me know if you have any handsome American friends looking for a relationship.”

On the way home, word had gotten out that I would be performing tomorrow morning. This came completely unexpectedly. Just last night, I had run into one of our department’s administrators in the elevator.

“Are you still taking guqin lessons?” she asked innocently.

“Yeah,” I replied. “They’re going quite well.”

Then, this morning, I woke up to a message from her supervisor—the international students’ advisor.

“Hi Andrew! I heard that you play guqin. Can you perform for us tomorrow morning? 8:30 am. Bring your own guqin; we’ll provide a table.”

I flopped back into my still-warm bed. I had barely been learning for three weeks and they wanted me to perform? But in this hierarchical system, I responded with the only word I could respond with: okay.

And now, word had spread to the other students.

“We’ll all come to support you!” Yongqi exclaimed.

“Yeah!” Sangwon chimed in. “I’m so excited!”

“What do you mean?” I was honestly surprised. “You hear me play guqin literally every single night.”

“Ah, it’s not the same,” he said. “A performance is much more exciting—and stressful for you—but still, that makes it fun to watch!”

We got home, and he helped me pick a song to perform (I only know three songs) and an outfit to wear. Meanwhile, my phone kept vibrating from the messages that were still going on. More and more people were hearing about the performance.

Let’s hope I don’t let them down.