Mondays are my day off here.

On Mondays, I have no household chores to do, and I close my laptop to take my research outside.

For my first outing, I went to Jiming Temple 雞鳴寺, a nunnery on the edge of Nanjing, adjacent to the city wall, which is in turn adjacent to Xuanwu Lake.

Upon arriving, I was surprised to see a line to purchase admission tickets. While I’m not a stranger to admission tickets for temples (they’re common for any historical temple in Japan), I doubted that Jiming Temple had anything on display that was worth charging admission for. National treasure statues? Probably not. Famous gardens? Unlikely.

But it was supposed to be a relatively popular destination in Nanjing, so I paid the 10 yuan and walked in.

It was old, that’s for sure.

The temple is built on a hill, so there are plenty of steps that lead to the various halls. While the buildings themselves seem somewhat old, the statues inside are probably no older than say, 20-30 years, and that’s if I’m being generous.

This is—however—not including the statues in the main shrine, which I couldn’t really see because it was closed when I visited.

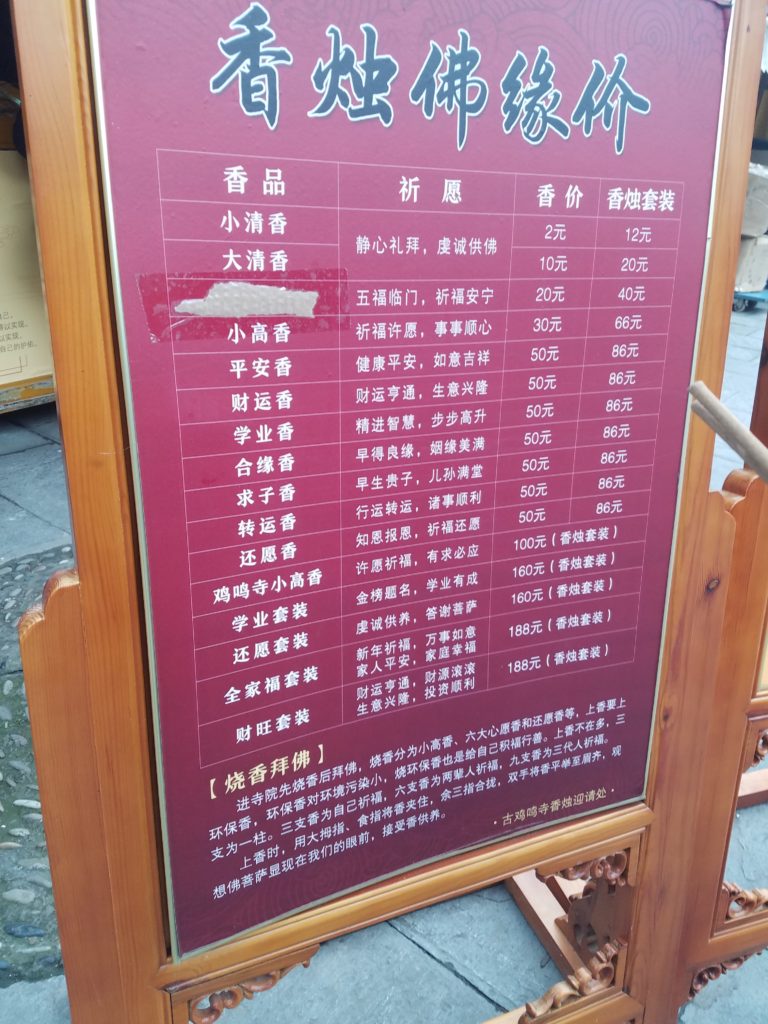

Overall, I was a bit disappointed in the state of affairs—the menu-like array of donation options, the lack of any Buddhist activities, and the proliferation of people tossing coins in donation boxes for spiritual protection.

In a way, it reminded me of the malaise I felt at a lot of Japanese temples, except here it was much less tasteful.

They had given me a few sticks of incense at the door, and I offered it in the one, giant censer they had outside. Again—nothing was very orderly about this, and my years of shrine attendant training kicked in as I began to arrange the incense so that there would at least be room for others to place their sticks.

I didn’t spend too much time in the temple, opting instead to sit in the temple library for a few hours. I was impressed by its collection, although it was understandably limited to Chinese language resources. It was still nice to have access to all sorts of rare books though.

They even had a guqin on display, although I decided not to mess with it since I didn’t want to be kicked out.

After my library session, I had lunch at the temple cafe before continuing on my Monday excursion. From the temple, I walked to the city wall and took a stroll along it until I reached Xuanwu Lake and looped around there.

At the lake, I encountered an interesting memorial to Guo Pu (276–324), an esteemed scholar and influential founder of Fengshui. Similar to how Abe no Seimei has his own shrine in Kyoto, Guo Pu’s cenotaph is surrounded by people’s wishes.

Now, from the temple to the city wall to the cenotaph, there were a lot of museum-like exhibits that were meant to be educational. The only issue was that they weren’t executed particularly skillfully. Display cases had objects without any sort of explanation or labeling, and although didactic panels were helpful, they didn’t interact with anything else in the exhibit.

So I left the park, disappointed in the exhibit design, but pleased by the misty scenery which transported me to what I imagine Song dynasty scholars would have seen while strolling by on a wintry afternoon.

On my home, I happened across a sluice which was used to divert water from the lake and into the city. This was an amazing little landmark with an exhibition that was actually well-done. The panels, the samples of bricks and pipes used in the sluice, and the diagrams of how the entire thing worked blended smoothly with the sections discussing the history and significance of the lake itself.

According to one panel, there was a monster in the lake which would terrorize the locals at night. Eventually, they decided to pray at Jiming Temple for some divine intervention, and Guanyin appeared that night to seal the monster at the bottom of the lake by agreeing to release it again in the morning.

As a result, the neighbors did not announce that it was morning ever again, and the monster—thinking that morning had yet to come—has been waiting patiently ever since. It is interesting because Jiming literally means “rooster’s crow.” That is, presumably, if a rooster were to crow near the lake and the lake monster were to hear it, it would be released from its watery prison and terrorize Nanjing again.

I’ve always been a fan of such myths, and whether or not they’re true is irrelevant to me. They make certain places significant to the locals, and that itself imbues the space with a solemn feeling that wouldn’t be there otherwise.

Next week, I’ll be meeting with a friend from Claremont I haven’t seen in about two years.